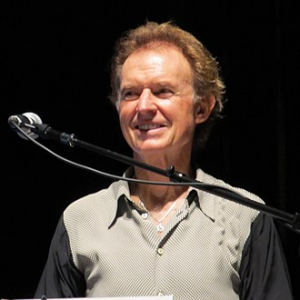

Gary Malcolm Wright

Gary Malcolm Wright (April 26, 1943 – September 4, 2023) was an American musician and composer best known for his 1976 hit songs “Dream Weaver” and “Love Is Alive“, and for his role in helping establish the synthesizer as a leading instrument in rock and pop music. Wright’s breakthrough album, The Dream Weaver (1975), came after he had spent seven years in London as, alternately, a member of the British blues rock band Spooky Tooth and a solo artist on A&M Records. While in England, he played keyboards on former Beatle George Harrison‘s triple album All Things Must Pass (1970), so beginning a friendship that inspired the Indian religious themes and spirituality inherent in Wright’s subsequent songwriting. His work since the late 1980s has embraced world music and the new age genre, although none of his post-1976 releases have matched the same level of popularity as The Dream Weaver.

A former child actor, Wright performed on Broadway in the hit musical Fanny before studying medicine and then psychology in New York and Berlin. After meeting Chris Blackwell of Island Records in Europe, Wright moved to London, where he helped establish Spooky Tooth as a popular live act. He also served as the band’s principal songwriter on their recordings – among them, the well-regarded albums Spooky Two (1969) and You Broke My Heart So I Busted Your Jaw (1973). His solo album Footprint (1971), recorded with contributions from Harrison, coincided with the formation of Wright’s short-lived band Wonderwheel, which included guitarist Mick Jones. Also, during the early 1970s, Wright played on notable recordings by B.B. King, Jerry Lee Lewis, Ringo Starr, Harry Nilsson and Ronnie Spector, while his musical association with Harrison endured until shortly before the latter’s death in 2001.

Wright turned to film soundtrack work in the early 1980s, including re-recording his most popular song, “Dream Weaver”, for the 1992 comedy Wayne’s World. Following Spooky Tooth’s reunion tour in 2004, Wright has performed live frequently, either as a member of Starr’s All-Starr Band, with his own live band, or on subsequent Spooky Tooth reunions. Wright’s most recent solo albums, including Waiting to Catch the Light (2008) and Connected (2010), have all been issued on his Larklio record label. In 2014, Jeremy P. Tarcher published Wright’s autobiography, Dream Weaver: Music, Meditation, and My Friendship with George Harrison.

Early life[edit]

Gary Wright was born and raised in Cresskill, New Jersey.[1] A child actor, he made his TV debut at the age of seven, on the show Captain Video and His Video Rangers, filmed in New York.[2] He appeared in TV and radio commercials before being offered a part in the 1954 Broadway production of the musical Fanny.[2] Wright played the role of Cesario, the son of Fanny, who was played by future Brady Bunch matriarch Florence Henderson.[3] He spent two years with the production, during which he performed with Henderson on The Ed Sullivan Show.[4]

Having studied piano and organ,[2] Wright led various local rock bands while attending[1] Tenafly High School in Tenafly, New Jersey.[5][6] In 1959, he made his first commercial recording, with Billy Markle at NBC Radio‘s New York studios.[7] Credited to Gary & Billy, the single “Working After School” was released on 20th Century Fox Records in 1960.[7]

Seeing music as “too unstable” a career choice, as he later put it,[4] Wright studied to become a doctor at the College of William & Mary in Virginia and New York University before attending Downstate Medical College for a year,[6] all the while continuing to perform with local bands.[4][8] Having specialized in psychology in New York,[2] he then went to West Germany in 1966[9] to complete his studies at the Free University of Berlin.[1]

Career[edit]

1967–1970: With Spooky Tooth[edit]

Wright has described his initial musical influences as “early R&B” – namely, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, James Brown and Bobby Bland – along with rock ‘n’ roll artists Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis, and the Beatles.[4] While in Europe in 1967, Wright abandoned his plans to become a doctor[4] and instead toured locally with a band he had formed, the New York Times.[1] When the latter supported the English group Traffic – at Oslo in Norway, according to Wright[8] – he met Island Records founder Chris Blackwell.[1] Wright recalls that he and Blackwell had a mutual friend in Jimmy Miller,[8] the New York-born producer of Island acts such as the Spencer Davis Group and Traffic.[10]

Blackwell invited Wright to London, where he joined English singer and pianist Mike Harrison and drummer Mike Kellie in their band Art (formerly the VIPs).[11] The group soon changed its name to Spooky Tooth,[1] with Wright as joint lead vocalist[8] and Hammond organ player.[12] While noting the band’s lack of significant commercial success over its career, The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll describes Spooky Tooth as “a bastion of Britain’s hard-rock scene”.[11]

Spooky Tooth’s first album was It’s All About, released on Island in June 1968.[2] Produced by Miller,[2] it contained the Wright-composed “Sunshine Help Me” and six songs he co-wrote with either Miller, Harrison or Luther Grosvenor,[13] the band’s guitarist.[14] Spooky Two, often considered the band’s best work, followed in March 1969, with Miller again producing.[15] Wright composed or co-composed seven of the album’s eight songs, including “That Was Only Yesterday” and “Better By You, Better Than Me“.[16] Spooky Two sold well in America but, like It’s All About, it failed to place on the UK’s top 40 albums chart.[17]

The third Spooky Tooth album was Ceremony, a Wright-instigated collaboration with French electronic music pioneer Pierre Henry,[14][18] released in December 1969.[11] Songwriting for all the tracks was credited to Henry and Wright,[19] after the latter had passed the band’s recordings on to Henry for what The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia terms “processed musique concrète overdubs”.[20]

Although Wright had traditionally provided an experimental influence within Spooky Tooth,[14] he regretted the change of musical direction, saying in a 1973 interview: “We should have really taken off after Spooky Two but we got into the absurd situation of letting Pierre Henry make the Ceremony album. Then he took it back to France and remixed it.”[17] With bass player Greg Ridley having already left the band in 1969 to join Humble Pie,[21] Wright departed in January 1970 to pursue a solo career.[17]

1970–1972: Solo career on A&M Records, Wonderwheel, and London session work[edit]

Extraction[edit]

After signing with A&M Records, Wright recorded Extraction (1970) in London[22] with musicians including Kellie, guitarist Hugh McCracken, bassist Klaus Voormann and drummer Alan White.[23] Wright co-produced the album with Andy Johns,[23] who had been the recording engineer on Spooky Two[24] and Ceremony.[19] The album included “Get on the Right Road”, which was issued as a single, and “The Wrong Time”,[25] co-written by Wright and McCracken.[26]

George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass[edit]

Through Voormann,[27] Wright was invited to play piano on former Beatle George Harrison‘s 1970 triple album All Things Must Pass.[3][28] Among what author Nicholas Schaffner later described as “a rock orchestra of almost symphonic proportions, whose credits read like a Who’s Who of the music scene”,[29] Wright was one of the album’s principal keyboard players, together with former Delaney & Bonnie organist Bobby Whitlock.[30] During the sessions, Wright and Harrison established a long-lasting friendship,[1][31] based on music and their shared interest in Indian religion.[3][32] In a 2009 interview with vintagerock.com, Wright described Harrison as “my spiritual mentor”;[8] author Robert Rodriguez writes of Wright’s “unique” place among musicians with whom Harrison collaborated at this time, in that Wright was neither an established star nor a friend from the years before Harrison achieved fame as a Beatle, and nor was he a “studio pro”.[33]

Wright played on all of Harrison’s subsequent solo albums during the 1970s,[34][35] as well as on other releases that the ex-Beatle produced for Apple Records.[36] These included two hit singles by Harrison’s former bandmate Ringo Starr over 1971–72, “It Don’t Come Easy” and “Back Off Boogaloo“, and a 1971 comeback single by ex-Ronette Ronnie Spector, “Try Some, Buy Some“.[37][nb 1]

Footprint[edit]

To promote Extraction, Wright formed the band Wonderwheel in April 1971,[38] with a lineup comprising guitarist Jerry Donahue – soon replaced by Mick Jones – Archie Legget (bass) and Bryson Graham (drums).[39][40] Donahue was among the many musicians on Wright’s second album, Footprint (1971),[41] along with George Harrison and All Things Must Pass contributors such as Voormann, White, Jim Gordon, Bobby Keys and John Barham.[22][42] Produced by Wright, the album included “Stand for Our Rights”, a call for social unity, song which was originally written for Johnny Hallyday under the name “Flagrant Délit” and was partly inspired by the Vietnam War,[43] “Two Faced Man” and “Love to Survive”.[44] In November 1971, Wright and Wonderwheel performed “Two Faced Man” on The Dick Cavett Show in New York, with Harrison accompanying on slide guitar.[45][nb 2] Wright has expressed gratitude for Harrison’s support during this stage of his career, citing the ex-Beatle’s uncredited production on Footprint[47] and his arranging the Dick Cavett Show appearance.[8] Despite this exposure,[45] like Extraction, the album failed to chart.[22][48]

Among other recordings over this period, Wright played piano on Harry Nilsson‘s 1972 hit “Without You“[33] and accompanied B.B. King, Starr, Gordon, Voormann and others on B.B. King in London (1971),[49] which included Wright’s composition “Wet Hayshark”.[50] He later participated in London sessions by Jerry Lee Lewis,[34] issued as the double album The Session (1973).[51] Wright also produced an eponymous album by folk rock band Howl the Good,[52] released on the Rare Earth label.[53]

Ring of Changes[edit]

In 1972, Wright moved to Devon with Wonderwheel to work on songs for a new album, titled Ring of Changes. With Tom Duffey having replaced Leggett on bass, the band recorded the songs at Olympic and Apple studios in London.[54] After issuing “I Know” as an advance single,[55] A&M chose to cancel the album.[56][nb 3] Wright also wrote the soundtrack for a film by former Olympic skier Willy Bogner, Benjamin (1972),[57] from which the German label Ariola Records released “Goodbye Sunday” as a single that year.[58] The full soundtrack album, recorded with Jones, Leggett and Graham,[59] was issued by Ariola in 1974.[60]

In September 1972, Wright decided to disband Wonderwheel and re-form Spooky Tooth.[61] Shortly before doing so, he participated in sessions for Harrison’s Living in the Material World (1973),[62] an album that Wright describes as “a beautiful masterpiece” and his favorite Harrison album.[63] Talking to Chris Salewicz of Let It Rock in early 1973, Wright explained his decision to abandon his solo career: “I think my main talent is getting the music together and arranging it. I’m not a showman and so I couldn’t be a Cat Stevens out front with just backing musicians, which I was expected to be with Wonderwheel.”[17] In his autobiography, however, Wright says that it was his disappointment at A&M’s rejection of Ring of Changes that led him to contact Blackwell about re-forming Spooky Tooth.[56]

1972–1974: Re-forms Spooky Tooth[edit]

The only members from the original lineup, Wright and Mike Harrison relaunched Spooky Tooth with Jones and Graham from Wonderwheel, and Chris Stewart,[11][14] formerly the bassist with English singer Terry Reid.[17] Salewicz visited the band while they were recording at Island Studios and remarked of Wright’s role in the group, “it is clear who is the leader of this brand of Spooky Tooth, and, I suspect, of the original, too”; Salewicz described Wright as “urbane, loquacious with the remnants of a New Jersey accent, and a touch of Dudley Moore about the face”.[17]

On their new album, You Broke My Heart So I Busted Your Jaw (1973),[11] Wright composed six of the eight tracks, including “Cotton Growing Man”, “Wildfire” and “Self Seeking Man”, and co-wrote the remaining two.[64] With the group’s standing having been elevated since 1970 – a situation that music journalist Steven Rosen likened at the time to the Yardbirds, the Move and other 1960s bands after their break-up[61] – Spooky Tooth toured extensively to promote the album.[38] Rolling Stone reviewer Jon Tiven praised Wright’s songwriting on You Broke My Heart, adding: “there is tremendous consistency to these originals … and ‘Wildfire’ is ample proof that Gary could have written for the Temptations if he really wanted to.”[65]

[We] could have definitely been like one of those bands, like Jethro Tull and all those people who were our contemporaries. I think [Spooky Tooth] didn’t have the steady momentum and upward drive. It stopped and started, broke up and then went back and broke up. It never really got enough behind it to really catapult it to success.[8]

– Wright in 2009, reflecting on Spooky Tooth’s lack of a commercial breakthrough

The band released a follow-up, Witness, in November 1973,[38] by which point Graham had departed, with Mike Kellie returning on drums.[61] By February 1974, Stewart and Harrison had also left.[38] In January that year, Wright accompanied George Harrison to India,[66] where they journeyed to Varanasi (Benares), the Hindu spiritual capital of India, and home to Harrison’s friend Ravi Shankar.[67] The visit would influence the spiritual quality of Wright’s lyrics when he returned to his solo career.[1]

In England, he and Harrison worked together on The Place I Love (1974),[68] the debut album by English duo Splinter.[69][70] In addition to playing keyboards, Wright served as what author Simon Leng terms “a sounding board and musical amanuensis” on the project,[71] which was the first album released on Harrison’s Dark Horse record label.[72] Wright regrouped with Spooky Tooth for a final album, The Mirror (1974), with Mike Patto as their new vocalist.[73] Following further personnel changes, The Mirror was issued by Goodear Records in the UK in October 1974, a month after Wright had disbanded the group.[38]

1975–1981: Solo career on Warner Bros. Records[edit]

The Dream Weaver[edit]

After Spooky Tooth’s break-up, Wright returned to New Jersey and began compiling songs for his third solo album.[74] Under the guidance of new manager Dee Anthony, he chose to sign with Warner Bros. Records, mainly because the company had no keyboard virtuosos among its other acts.[74] Wright says that it was while routining his songs with all his stage equipment set up – Hammond organ, Hohner Clavinet, Fender Rhodes electric piano, Minimoog and ARP String Ensemble – together with a drum machine, that he decided to record the album “all on keyboards”, without guitars.[8] He acknowledges that artists such as Stevie Wonder had similarly released keyboard-dominated music, but “[Wonder] used brass and he used other things as well”.[6] On Wright’s debut album for Warner Bros., The Dream Weaver (1975),[2] he, David Foster and Bobby Lyle played a variety of keyboard instruments, supported only by drummers Jim Keltner and Andy Newmark,[75] apart from a guitar part on the track “Power of Love” by Ronnie Montrose.[76] Jason Ankeny of AllMusic describes The Dream Weaver as “one of the first [rock albums] created solely via synthesizer technology”.[1]

I mean … I’m an overnight success in ten years, right? I’ve been through periods of self-doubt, wondering whether or not I wanted to stay an artist … but I guess, like in all things, it’s timing. The right timing, the right songs and strong management at last.[74]

– Wright commenting in 1976 on the unexpected success of The Dream Weaver

The album was issued in July 1975 and enjoyed minimal success in America until the release of its second single, “Dream Weaver“, in November.[74] The song, which Wright had written on acoustic guitar[74] after his visit to India with Harrison,[77] went on to peak at number 2 on the Billboard Hot 100[78] and number 1 on the Cash Box singles chart.[79] Becoming Wright’s biggest hit, “Dream Weaver” sold over 1 million copies in the US and was awarded a Gold disc by the RIAA in March 1976.[79] The album climbed to number 7 on the Billboard 200[80] and was certified double Platinum.[2] “Love Is Alive“, originally the album’s lead single,[74] then hit number 2 on the Hot 100, and “Made to Love You” peaked at number 79.[78] Although neither The Dream Weaver or its singles charted in the UK, the album was a big seller in West Germany,[74] where, Wright says, Spooky Tooth had been “the number one band” during 1969.[8]

Following the album’s release, Wright toured extensively with a band comprising three keyboard players and a drummer.[74] His elder sister Lorna, also a professional singer, joined the tour band as his backing vocalist.[81] Subsidized by synthesizer manufacturers Moog and Oberheim,[6] Wright became one of the first musicians to perform with a portable keyboard, in the style of Edgar Winter.[74] Shawn Perry of vintagerock.com credits Wright with being “as responsible for the emergence of the synthesizer as a mainstream instrument as Keith Emerson and … Rick Wakeman“,[8] while Robert Rodriguez describes Wright as a pioneer in both “the integration of synthesizers into analog recordings” and the use of the keyboard–guitar hybrid known as the keytar.[33]

Among his live performances in 1976, Wright shared the bill with Yes and Peter Frampton at the US Bicentennial concert held at JFK Stadium, Philadelphia, playing to a crowd estimated at 120,000.[82] Wright then supported Frampton on a European tour, by which time a fourth keyboard player had been added to the band.[83] Amid this success, A&M issued That Was Only Yesterday (1976)[11] – a compilation containing tracks from Wright’s albums for the label and selections by Spooky Tooth[84] – which charted at number 172 in America.[80]

The Light of Smiles[edit]

Wright started recording his follow-up to The Dream Weaver in summer 1976, before which Chris Charlesworth of Melody Maker reported that it would be “a logical development” of its predecessor and “again based entirely around what he can do with various types of keyboards”.[74] Titled The Light of Smiles (1977), the album included “I Am the Sky”, for which Wright gave a songwriting credit to the late Indian guru and Kriya Yoga teacher,[85] Paramahansa Yogananda.[86] The latter’s poem “The Light of Smiles”, taken from his book Metaphysical Meditations,[87] appeared on the inner sleeve to Wright’s new album.[88] Wright had acknowledged the guru as his inspiration for the title of The Dream Weaver,[76] and he later said of Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi: “It’s a fantastic book and you won’t want to put it down when you start reading it. Even, not from a spiritual point of view, but as a piece of literature, it’s a total classic …”[8]

Produced again by Wright, The Light of Smiles featured Wright, Foster, Peter Relich and others on a range of keyboard instruments, including Moog, Oberheim and ARP synthesizers, and drumming contributions from Art Wood and Keltner.[89] Issued by Warner Bros. in January 1977,[90] neither the album nor its lead single, “Phantom Writer”, matched the popularity of Wright’s earlier releases for the label.[1] On the US Billboard charts, The Light of Smiles climbed to number 23,[80] while “Phantom Writer” peaked at number 43.[78]

Touch and Gone, Headin’ Home and The Right Place[edit]

Wright continued to record albums for Warner Bros. until 1981, with only limited commercial success.[1] Released in late 1977, Touch and Gone charted at number 117 in America,[80] with its title track reaching number 73.[78] Headin’ Home, which AllMusic’s Joe Viglione describes as “an album seemingly driven by a serious relationship in crisis”,[91] peaked at number 147 in 1979.[80] In between these two albums, Wright played on “If You Believe“, a song he co-wrote with Harrison in England on New Year’s Day 1978,[92] which appeared on Harrison’s eponymous 1979 album.[93]

Wright’s last chart success in America was in 1981,[2] when his album The Right Place, co-produced with Dean Parks,[94] climbed to number 79.[80] The single “Really Wanna Know You“, which Wright co-wrote with Scottish singer Ali Thomson,[95] peaked at number 16 that year.[78] A second single from the album, “Heartbeat”, appeared on Billboard‘s Bubbling Under listings, at number 107.[96]

1982–2000: Film soundtracks and world music[edit]

Wright’s subsequent releases focused on film soundtracks and forays into world music.[1] After writing the score for Alan Rudolph‘s 1982 thriller Endangered Species,[97] he supplied the soundtrack to another skiing-themed movie by Willy Bogner,[98] Fire and Ice (1986), which hit number 1 on the German albums chart.[1] Wright also contributed the song “Hold on to Your Vision” to the soundtrack of Cobra, a 1986 action movie starring Sylvester Stallone.[99]

Among notable cover versions of Wright’s songs during this period, Chaka Khan recorded “Love Is Alive” (retitled “My Love Is Alive”) for her 1984 album I Feel for You,[100] which became an RIAA-certified million-seller.[101] A cover of his Spooky Tooth composition “Better By You, Better Than Me”, by English heavy metal band Judas Priest, was at the center of a 1990 court case regarding subliminal messages in song lyrics, after two Nevadan teenagers had enacted a suicide pact five years before.[102] From 1989 through to the late 1990s, samples of Wright’s “Dream Weaver”, “Love Is Alive” and “Can’t Find the Judge” variously featured in songs by popular rap and hip-hop artists Tone Lōc, Dream Warriors, 3rd Bass and Mýa.[103]

Wright himself re-recorded “Dream Weaver” for the 1992 comedy Wayne’s World,[1] the soundtrack album for which topped the US charts.[104] The song has since appeared in the films The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996) and Toy Story 3 (2010).[99] He later provided “We Can Fly” for another Bogner film, Ski to the Max,[105] released in IMAX cinemas in October 2000.[106]

Who I Am, First Signs of Life and Human Love[edit]

In 1988, Wright released Who I Am on A&M-distributed[107] Cypress Records.[2] Among the album’s contributors were Western musicians such as Harrison, White and Keltner,[108] a group of South Indian percussionists,[105] and Indian classical violinists L. Subramaniam and L. Shankar.[1] The previous year, Wright had contributed to Harrison’s album Cloud Nine (1987), for which he co-wrote “That’s What It Takes” with Harrison and Jeff Lynne,[109] and played keyboards on songs such as “When We Was Fab“.[110] One of the tracks from Who I Am, “Blind Alley”, was used in the 1988 horror film Spellbinder.[111]

Wright’s next solo album was First Signs of Life (1995), recorded in Rio de Janeiro and at his own[9] High Wave Studios in Los Angeles,[112] and issued on the Triloka/Worldly record label.[15][113] The album combined Brazilian rhythms[15] with elements of African vocal tradition, creating what AllMusic’s reviewer describes as “an infectious worldbeat hybrid”, where “the musicians’ performances radiate sincerity and joy”.[114] First Signs of Life featured guest appearances from drummer Terry Bozzio, Brazilian guitarist Ricardo Silveira and Harrison.[114] The song “Don’t Try to Own Me”, co-written with Duane Hitchings, was later included on Rhino Records‘ Best of Gary Wright: The Dream Weaver – a 1998 compilation spanning his solo career from 1970 onwards, and featuring extensive liner notes by Wright.[115]

Human Love (1999) included new versions of “Wildfire” and “The Wrong Time”,[116] as well as “If You Believe in Heaven”, a song written with Graham Gouldman that had first appeared on Best of Gary Wright.[115] The album was co-produced by German world-music producer Marlon Klein[117] and released on the High Wave Music label.[113][116] Contributors to the sessions, held at High Wave and at Exil Musik in Bielefeld, included Hindustani classical vocalist Lakshmi Shankar, Lynne and German composer Roman Bunka.[117]

Later career[edit]

Having dedicated much of his time during the 1990s to his family, Wright subsequently resumed a more active musical career, starting with Spooky Tooth’s 2004 reunion.[9] Their album and DVD Nomad Poets Live in Germany (2007) features Wright, Mike Harrison and Kellie from the band’s original lineup.[118] Wright’s past work has continued to inspire rap and dance tracks in the 21st century; samples of “Heartbeat” appear in songs by Jay-Z and Diam’s, while Topmodelz covered the song in 2007.[103] Other artists who have used samples from Wright’s 1975–81 recordings include Dilated Peoples, Atmosphere, Infamous Mobb, T.I. and Armand Van Helden,[103] the last of whom incorporated part of “Comin’ Apart” (from The Right Place) in his 2004 club hit “My My My“.[97] In addition, Eminem used “interpolations” from Spooky Tooth’s “Self Seeking Man” in his song “Spend Some Time” (released on Encore in 2004).[119]

In the summer of 2008, Wright joined Ringo Starr & His All-Starr Band for a North American tour, with Edgar Winter also in the lineup.[120] The All-Starr Band’s album and DVD Live at the Greek Theatre 2008 (2010) includes Wright’s performance of “Dream Weaver”.[121] Wright later described the tour as “a lot of fun” and “a big boost” for his career.[8]

Waiting to Catch the Light and Connected[edit]

Two solo releases by Wright followed in late 2008, including the new-age album Waiting to Catch the Light.[9] A collection of instrumental pieces from “several years” before, he describes it as “an atmospheric, ambient music kind of an album”, performed on “vintage analog synthesizers … all [recorded] on analog tape”.[8] Also issued on Larkio,[113] Wright’s own record label,[9] the EP The Light of a Million Suns consisted of unreleased tracks from his previous album projects, together with a new version of “Love Is Alive”, sung by his son Dorian.[8]

In May 2009, Wright rejoined Spooky Tooth to participate in a series of London concerts celebrating the 50th anniversary of Island Records’ founding,[122] before performing further shows with the band in Germany.[8] In June the following year, he released the album Connected,[3] which marked a return to his more pop- and rock-oriented sound of the 1970s.[9][123] Starr, Joe Walsh and Jeff “Skunk” Baxter made guest appearances on the track “Satisfied”,[123] which Wright co-wrote with songwriter Bobby Hart.[9] As a posthumous tribute to his friend George Harrison, the Deluxe Digital Edition of Connected included “Never Give Up”,[124] which he and Harrison recorded in 1989, while the iTunes version added “To Discover Yourself”, a song that the two musicians wrote together in 1971.[123] Wright recorded the latter song on the day of Harrison’s death in November 2001.[3][123] He also contributed to Martin Scorsese‘s 2011 documentary George Harrison: Living in the Material World[125] and supplied personal reminisces and family photographs for Olivia Harrison‘s book of the same title.[126]

In 2010 and 2011, Wright toured again with Ringo Starr & His All-Starr Band.[120] Following a summer 2011 tour of Europe with Starr, Wright participated in the Hippiefest US tour with artists such as Felix Cavaliere, Mark Farner, Dave Mason and Rick Derringer,[6] before returning to Europe for shows with his own band late that year.[9]

Personal life[edit]

Wright resided in Palos Verdes Estates, California with wife Rose, whom he married in 1985.[9] He was previously married to Christina,[127] who, as Tina Wright, received co-writing credits on Wright’s songs “I’m Alive” (from The Mirror),[128] “Feel for Me” (The Dream Weaver)[76] and “I’m the One Who’ll Be by Your Side” (Headin’ Home).[91] He has two adult sons, Dorian and Justin.[9] Justin is a member of the band Intangible.[129] Wright has a sister, Lorna Dune, who recorded the song Midnight Joey. The song was an answer song to Joey Powers’ Midnight Mary in 1962.[130]

Wright has spoken out on the importance of creative opportunities for children in the public educational system,[4] and expressed his opposition to the prevalence of free music downloading and its disadvantage to artists.[34] In 2008, he voiced his support for Barack Obama‘s presidential campaign, during which “Dream Weaver” was a song adopted for the Democratic National Convention in Denver, Colorado.[131] That year, Wright discussed the message behind “Dream Weaver” with Huffington Post writer and political activist Howie Klein, saying: “With Wayne’s World and all that, the perception of the song’s meaning got a little bit changed for a lot of people. It’s a very spiritual song. ‘Dream Weaver’ is really a song whose lyrical content is about the consciousness of the Universe: God moving us through the night – delusion and suffering – into the Higher Realms.”[131]

In August 2014, Wright announced the imminent publication of his autobiography, Dream Weaver: Music, Meditation, and My Friendship with George Harrison.[132] Coinciding with the book’s release, Wright’s Warner Bros. albums were reissued for digital download.[133]

Wright’s death was announced on September 4, 2023. He was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia five years before his death.[134]

Discography[edit]

Albums[edit]

- 1970 Extraction (1970)

- 1971 Footprint (1971)

- 1975 The Dream Weaver (1975) US #7 – US: 2× Platinum[135]

- 1977 The Light of Smiles (1977) US #23

- 1977 Touch and Gone (1977) US #117

- 1979 Headin’ Home (1979) US #147

- 1981 The Right Place (1981) US #79

- 1988 Who I Am (1988)

- 1995 First Signs of Life (1995)

- 1999 Human Love

- 2008 Waiting to Catch the Light

- 2010 Connected

Collaborations[edit]

- 1972 That Was Only Yesterday (with Spooky Tooth)

- 1972 Ring of Changes (with Wonderwheel)

- 2004 Down This Road (Gary Wright & Leah Weiss)

Soundtracks[edit]

- 1974 Benjamin – The Original Soundtrack of Willy Bogner’s Motion Picture

- 1982 Endangered Species (soundtrack)

- 1986 Fire and Ice (soundtrack)

Compilations[edit]

- 1998 The Best of Gary Wright: The Dream Weaver

- 2003 The Essentials

- 2017 Greatest Hits

Extended play[edit]

- The Light of a Million Suns (2008)

Singles[edit]

| Year | Song | Peak chart positions | Certification | Album | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Hot 100 |

U.S. A/C |

U.S. R&B |

AUS [136] |

||||

| 1971 | “Get on the Right Road” | — | — | — | — | Extraction | |

| “Stand for Our Rights” | — | — | — | — | Footprint | ||

| 1972 | “Two Faced Man” | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1976 | “Dream Weaver“ | 2 | 14 | — | 24 |

|

The Dream Weaver |

| “Love Is Alive“ | 2 | — | 98 | 71 | |||

| “Made to Love You” | 79 | — | — | — | |||

| 1977 | “Phantom Writer” | 43 | — | — | — | The Light of Smiles | |

| “The Light of Smiles” | — | — | — | — | |||

| “Are You Weepin'” | — | — | — | — | |||

| “Touch and Gone” | 73 | — | — | — | Touch and Gone | ||

| “Starry Eyed” | — | — | — | — | |||

| “Something Very Special” | — | — | — | — | |||

| 1979 | “I’m the One Who’ll Be by Your Side” | — | — | — | — | Headin’ Home | |

| 1981 | “Really Wanna Know You“ | 16 | 32 | — | 49 | The Right Place | |

| “Heartbeat” | 107 | — | — | — | |||

| “Close to You” | — | — | — | — | |||

| 1988 | “Take a Look” | — | — | — | — | Who I Am | |

| 1989 | “It Ain’t Right” | — | — | — | — | ||

Notes[edit]

- ^ Wright recalls that he had been asked to play on John Lennon‘s Imagine album (1971), but he was unable to attend the sessions.[3][27]

- ^ The performance, along with Harrison’s interview with host Dick Cavett, was issued by Shout! Factory in 2005 on the DVD The Dick Cavett Show – Rock Icons.[46]

- ^ While Rolling Stone lists Ring of Changes as a 1972 release,[2] A&M’s archives site suggests that the album may have been withdrawn.[25]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ankeny, Jason. “Gary Wright”. AllMusic. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, p. 1094.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Parker, Melissa (September 28, 2010). “Gary Wright Interview: The ‘Dream Weaver’ Gets ‘Connected,’ Tours with Ringo Starr”. Smashing Interviews. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f “Gary Wright Interview (100.3 The Sound)”. YouTube. September 23, 2010. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ “Music Notes”. The Star-Ledger. November 16, 2000. p. 71.

Singer-songwriter-keyboardist Gary Wright, who grew up in Cresskill and went to Tenafly High School, will perform in New York tonight for the first time in 20 years.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Voger, Mark (July 29, 2011). “Hippiefest: Gary Wright Interview”. nj.com. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Markle, Gil. “Gary Wright”. studiowner.com. Diary of a Studio Owner. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Perry, Shawn. “The Gary Wright Interview”. vintagerock.com. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Von Brucken Fock, Menno. “Interviews: Gary Wright”. dprp.net. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ “Jimmy Miller, 52, Recording Producer”. New York Times. October 24, 1994. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, p. 938.

- ^ Leng, pp. 90, 91.

- ^ Anderson, Jason. “Spooky Tooth It’s All About“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Graff & Durchholz, p. 1248.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Graff & Durchholz, p. 1249.

- ^ DeGagne, Mike. “Spooky Tooth Spooky Two“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Salewicz, Chris (February 1973). “Spooky Tooth Together Again”. Let It Rock. Available at Rock’s Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Allan, Mark. “Pierre Henry/Spooky Tooth Ceremony: An Electric Mass“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Sleeve and label credits, Celebration LP (US promo). A&M Records, 1970; produced by Spooky Tooth & Pierre Henry.

- ^ The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, pp. 938–39.

- ^ The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, pp. 462, 938.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Leng, p. 108.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Gary Wright Extraction: Credits”. AllMusic. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Sleeve credits, Spooky Two LP. Island Records, 1969; produced by Jimmy Miller.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Gary Wright”. On A&M Records. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Sleeve credits, Extraction LP. (A&M Records, 1970; produced by Gary Wright & Andy Johns).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wright, Gary (September 29, 2014). “When Gary Wright Met George Harrison: Dream Weaver, John and Yoko, and More”. The Daily Beast. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ Leng, p. 91.

- ^ Schaffner, p. 142.

- ^ Leng, p. 82fn.

- ^ Rodriguez, p. 87.

- ^ Leng, pp. 91, 108, 124–25, 209.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Rodriguez, p. 88.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Barnes, Alan (December 4, 2010). “Gary Wright Interview with Alan Barnes Part 1”. YouTube. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Leng, pp. 125, 153, 182–83, 190, 209.

- ^ Wright, p. 109.

- ^ Spizer, pp. 255, 294, 297–98.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Robinson, Alan. “Spooky Tooth Biography”. spookytooth.sk. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Terol, Miguel (September 17, 2001). “Bryson Graham”. The Musicians’ Olympus. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Wright, p. 98.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 201.

- ^ Wright, pp. 97, 99.

- ^ Liner notes , Best of Gary Wright: The Dream Weaver. Rhino Records, 1998; produced by Gary Wright, Gary Peterson & David McLees.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 105–06.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rodriguez, pp. 88, 319–20.

- ^ Galbraith IV, Stuart (August 16, 2005). “The Dick Cavett Show – Rock Icons”. dvdtalk.com. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ Flucke, Mojo (April 3, 2009). “The Popdose Interview: Gary ‘Dream Weaver’ Wright”. Popdose. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ Wright, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Randall, Brackett & Hoard, p. 453.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, p. 105.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. “Jerry Lee Lewis The Session“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ “Credits: Howl the Good Howl the Good“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ “Howl the Good – Howl the Good (Vinyl, LP, Album)”. Discogs. August 16, 1972. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Wright, pp. 112–13.

- ^ Sleeve text, “Ring of Changes” promotional single. A&M Records, 1972; produced by Gary Wright.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wright, p. 113.

- ^ “Gary Wright – Benjamin – The Original Soundtrack of Willy Bogner’s Motion Picture (Vinyl, LP, Album)”. Discogs. August 16, 1972. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ “Gary Wright – Goodbye Sunday”. Discogs. August 16, 1972. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Sleeve credits, Benjamin – The Original Soundtrack of Willy Bogner’s Motion Picture LP. Ariola Records, 1974; produced by Willy Bogner.

- ^ “Gary Wright”. musicknockout.net. Archived from the original on June 18, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Rosen, Steven (November 1973). “The Return of Spooky Tooth”. Music World. Available at Rock’s Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Leng, pp. 124–25.

- ^ Wright, p. 107.

- ^ Label credits, You Broke My Heart So I Busted Your Jaw LP. Island Records, 1973; produced by Gary Wright & Spooky Tooth.

- ^ Tiven, Jon (June 21, 1973). “Spooky Tooth: You Broke My Heart So I Busted Your Jaw“. Rolling Stone. Available at Rock’s Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Wright, pp. 120–21, 123.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, p. 258.

- ^ Leng, pp. 143, 144.

- ^ Schaffner, p. 179.

- ^ Wight, pp. 109, 110.

- ^ Leng, p. 144.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 200–01, 205–06, 311.

- ^ The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, pp. 938, 939.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Charlesworth, Chris (June 5, 1976). “Gary Wright: Wright at Last”. Melody Maker. Available at Rock’s Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ “Gary Wright The Dream Weaver: Credits”. AllMusic. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Sleeve credits, The Dream Weaver LP. Warner Bros. Records, 1975; produced by Gary Wright.

- ^ “Gary Wright > Inspiration”. thedreamweaver.com. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “Gary Wright: Chart History”. billboard.com. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Murrells, p. 365.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f “Gary Wright: Awards”. AllMusic. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Wright, p. 20.

- ^ Welch, Chris (June 26, 1976). “Yes, Peter Frampton, Gary Wright: JFK Stadium, Philadelphia”. Melody Maker. Available at Rock’s Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Salewicz, Chris (October 30, 1976). “Peter Frampton: Empire Pool, Wembley, London”. NME. Available at Rock’s Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ “Gary Wright/Spooky Tooth – That Was Only Yesterday”. Discogs. August 16, 1972. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ Bowden, p. 629.

- ^ “Gary Wright The Light of Smiles“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ “The Light of Smiles”. lightworkers.org. Archived from the original on March 20, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ Inner sleeve, The Light of Smiles LP. Warner Bros. Records, 1977; produced by Gary Wright.

- ^ “Gary Wright The Light of Smiles: Credits”. AllMusic. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ Freedland, Nat (reviews ed.) (January 15, 1977). “Top Album Picks”. Billboard. p. 80. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Viglione, Joe. “Gary Wright Headin’ Home“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ George Harrison, p. 358.

- ^ Leng, pp. 199, 209.

- ^ Label credits, The Right Place LP. Warner Bros. Records, 1981; produced by Gary Wright & Dean Parks.

- ^ Stone, Doug. “Ali Thomson”. AllMusic. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ “Songs that charted under the Hot 100: 1981”. rateyourmusic.com. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Gary Wright > Biography”. thedreamweaver.com. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ “Willy Bogner Film: Action Videos & Sport Movies”. bogner.com. Archived from the original on April 1, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “City of Largo, Florida / Events Calendar / Gary Wright”. largo.com. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Henderson, Alex. “Chaka Khan I Feel for You“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll, p. 536.

- ^ Moore, Thomas E. (November–December 1996). “Scientific Consensus and Expert Testimony: Lessons from the Judas Priest Trial”. csicop.org. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Gary Wright Music Sampled by Others”. whosampled.com. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ “Original Soundtrack Wayne’s World: Awards”. AllMusic. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Gary Wright Bio”. utopiaartists.com. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ “Ski to the Max”. imax.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ “Cypress Records”. On A&M Records. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ “Gary Wright Who I Am: Credits”. AllMusic. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Leng, pp. 248, 249.

- ^ Kordosh, J. (December 1987). “Fab! Gear! The George Harrison Interview (part 1)”. Creem. Available at Rock’s Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ “Spellbinder Soundtrack (1988) OST”. ringostrack.com. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ Album booklet, First Signs of Life CD. Triloka/Worldly, 1995; produced by Gary Wright & Franz Pusch.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Gary Wright > Discography”. thedreamweaver.com. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Gary Wright First Signs of Life“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Stone, Doug. “Gary Wright Best of Gary Wright: The Dream Weaver“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Gary Wright Human Love“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Album booklet, Human Love CD. High Wave Music, 1999; produced by Gary Wright, Marlon Klein, Bernhart Locker & Franz Pusch.

- ^ “Spooky Tooth Nomad Poets Live in Germany“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ Album notes, Encore CD. Aftermath Entertainment, 2004; produced by Dr. Dre, Eminem, Luis Resto, Mike Elizondo & Mark Batson.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Biography”. ringostarr.com. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. “Ringo Starr & His All Starr Band Live at the Greek Theatre 2008“. AllMusic. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ “Island Records 50th Anniversary – A Celebration”. earbender.com. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Greco, Ralph Jr. “Gary Wright Connected – CD Review”. vintagerock.com. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ “Gary Wright – Connected (Deluxe Digital Edition) (File, Album)”. Discogs. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ End credits (disc 2), George Harrison: Living in the Material World DVD. Roadshow Entertainment, 2011; produced by Olivia Harrison, Nigel Sinclair & Martin Scorsese; directed by Martin Scorsese.

- ^ Olivia Harrison, pp. 258–59, 398.

- ^ Badman, p. 79.

- ^ Sleeve credits, The Mirror LP. Island Records, 1974; produced by Gary Wright, Mick Jones & Eddie Kramer.

- ^ “Intangible”. intangiblemusic.com. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ^ Roger Ashby Oldies Show Dec. 3/4, 2022

- ^ Jump up to:a b Klein, Howie (September 7, 2008). “‘Dream Weaver’ – Why Gary Wright Backs Barack Obama”. The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ “Gary Wright to reveal all about George Harrison friendship in new book”. Daily Express. August 13, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ Gundersen, Edna (August 27, 2014). “Gary Wright’s ‘Dream Weaver’ memoir out Oct. 2”. USA Today. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ Reynolds, Dolan (September 4, 2023). “‘Dream Weaver’ singer Gary Wright has died at 80”. FOX8 WGHP. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Gold & Platinum”. RIAA. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 343. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

Sources[edit]

- Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- Bowden, Henry Warner (1993). Dictionary of American Religious Biography. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-27825-3.

- Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, Michigan: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- Harrison, George (2002). I Me Mine. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-3793-9.

- Harrison, Olivia (2011). George Harrison: Living in the Material World. New York: Abrams. ISBN 978-1-4197-0220-4.

- Leng, Simon (2006). While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-1-4234-0609-9.

- Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd edn). London: Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll. New York: Fireside/Rolling Stone Press. 1995. ISBN 0-684-81044-1.

- Randall, Mac; Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds) (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th edn). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Rodriguez, Robert (2010). Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles’ Solo Years, 1970–1980. Milwaukee: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Spizer, Bruce (2005). The Beatles Solo on Apple Records. New Orleans: 498 Productions. ISBN 0-9662649-5-9.

- Wright, Gary (2014). Dream Weaver: A Memoir; Music, Meditation, and My Friendship with George Harrison. New York: Tarcher/Penguin. ISBN 978-0-399-16523-8.

External links[edit]

- Official website www.TheDreamWeaver.com

- Gary Wright biography by Jason Ankeny, discography and album reviews, credits & releases at AllMusic

- Gary Wright discography, album releases & credits at Discogs

- Gary Wright albums to be listened on Spotify

- Gary Wright albums to be listened on YouTube

- Career retrospective interview from November 2015 with Pods & Sods at PodsOdCast.com

- Recent deaths

- 1943 births

- 2023 deaths

- American expatriates in the United Kingdom

- American hard rock musicians

- American male singers

- American new-age musicians

- American rock keyboardists

- American soft rock musicians

- College of William & Mary alumni

- New York University alumni

- People from Cresskill, New Jersey

- Progressive rock keyboardists

- Spooky Tooth members

- SUNY Downstate Medical Center alumni

- Tenafly High School alumni

- American world music musicians

- People from Palos Verdes Estates, California

- American organists

- American male organists

- American rock pianists

- American male pianists

- A&M Records artists

- Island Records artists

- Warner Records artists

- Devotees of Paramahansa Yogananda

- 20th-century American pianists

- 21st-century American keyboardists

- 21st-century organists

- 20th-century American keyboardists

- Ringo Starr & His All-Starr Band members